If there’s a symbol of the environmental destructiveness of our consumer culture, it’s plastic, made from carbon-spewing petroleum products. But what if bags, bottles, and other plastics could help save the environment, not destroy it? What if your laptop computer, smartphone case, and office furniture, rather than emitting planet-warming greenhouse gases, stored them instead?

They will soon.

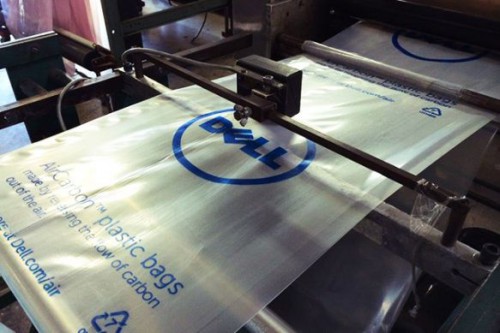

A Southern California company called Newlight Technologies has developed a way to make plastic from carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. It’s called AirCarbon, and this fall, Dell Latitude laptops manufactured near El Paso, Tex., will be shipped in a Newlight AirCarbon plastic bag made from greenhouse gases that would otherwise be heating the planet. Virgin Mobile, meanwhile, has struck a deal to sell AirCarbon phone cases through Sprint, and furniture maker KI will start using AirCarbon plastic in its products.

“This has the potential not to just change our industry but the world at large,” says Dick Resch, chief executive of Green Bay, Wis.–based KI. “We’re taking pollutants out of the air and turning them into plastics that can be recycled. It’s pretty amazing on several fronts.”

Oliver Campbell, Dell’s head of worldwide procurement for packaging, said that testing by independent laboratories not only verified that AirCarbon plastic is carbon negative but that it is significantly cheaper than petroleum-based plastic.

“This is a big paradigm shift,” says Campbell. “With technology like AirCarbon, we’re starting to leave the planet in better shape than we found it.”

AirCarbon also helps solve a climate change conundrum: how to contain greenhouse gas emissions while promoting economic growth, particularly in poor, fossil fuel–dependent developing countries.

The creators of this fantastic plastic are a pair of Orange County high school buddies named Mark Herrema and Kenton Kimmel.

As Herrema prepared to graduate from Princeton University 11 years ago, he had a revelation that could have come straight out of a 21st-century version of the famous scene in The Graduate. (An executive corners a newly graduated Dustin Hoffman at a Los Angeles cocktail party in 1967 and offers a bit of advice: “I want to say one word to you. Just one word. Plastics. There’s a great future in plastics.”)

In this case, Herrema was reading a Los Angeles Times story about efforts to contain emissions of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, from dairy cows. A lightbulb went off. Plastics.

“I thought, Why are we just emitting all the carbon in the air or taxing it or putting it in the ground when most of the materials we are making today are made from carbon,” Herrema, Newlight’s chief executive, recalls at the company’s Costa Mesa, Calif., headquarters, which are next to an auto repair shop. “Why not use this as a resource to make plastic?”

It was not a new idea. But past efforts foundered on a fundamental problem: cost. It took one pound of a pricey catalyst to create one pound of really expensive plastic. Herrema and Kimmel, Newlight’s chief technology officer, ran into the same roadblock.

“I spent my entire 20s in this building trying to make this work,” says Herrema, 32, a self-described “science nerd” who looks more like the Southern California surfer that he is. “Eventually we had a breakthrough, and the breakthrough was a new kind of catalyst that wouldn’t turn itself off at this one-to-one ratio.”

That was in 2010. Newlight’s new catalyst initially produced plastic at a three-to-one ratio. But the plastic wasn’t exactly ready for prime time. Herrema and Kimmel made their first chair for KI’s Resch, an early investor in Newlight. The executive picked up the chair and snapped it in half with his hand. Today Newlight is producing 10 pounds of plastic for every pound of catalyst, and all the chairs in the company’s offices were made by KI from AirCarbon.

At the company’s research lab, methane gas—yes, from cows like those Herrema read about in the newspaper—is mixed with air in a steel tank. Newlight’s patented biocatalyst then strips out the carbon from the methane and chains the molecules together to form different grades of plastic resin. At the end of the production line, the resin is chopped into pellets. Newlight sells the pellets to manufacturers to be molded into products. The company operates a plant in California and is building another one in the Midwest that will produce 50 million pounds of plastic annually. The company will obtain greenhouse gases from landfills or farms.

In one corner of the lab, scientists are experimenting with creating an AirCarbon replacement for plastic water bottles and foam packaging, those other ubiquitous scourges of modern life.

Dell’s Campbell says the computer maker next wants to use AirCarbon to replace foam packaging and, eventually, plastic parts in its computers and servers. The biggest challenge Newlight faces, he says, is scaling up production to meet the demand of global corporations like Dell.

Herrema says the company is in discussions with potential investors and partners that would allow Newlight to start meeting that market.

“Why would you ever use a plastic bag that emits carbon again?” says Herrema. “We want to see this replace plastics everywhere.”

[via take part]